The River Tame ran through parts of the town, mostly underground. The waters remained relatively clean until the middle of the 19th century, when first Chances & Hunt and then Albright and Wilson opened their chemical works. Phosphorous, sulphur and alkali’s were made in vast quantities here, releasing chlorine, ammoniacal liquors and sulphocyanide into the small river.

Iron and steel production involved a process of cleaning called ‘pickling’ which used acids, which often ended up in the canals. People clearly remember two huge mounds of solid waste called The Blue Billies. 150,000 cubic yards of chemical toxic waste right next to one of the tributaries of the river. When it rained, the Blue Billies would flood, turning the water yellow and bringing the smell of rotten eggs.

Bill Parkes recalls: ‘They used to dump the water in there that they used for pickling the tubes. When they cleaned the vats out periodically, there were thousands of gallons of water. Well the water had to be dumped, chemicals and everything went in there. Blue Billy was two pools. If you go down to the motorway island and look across left, it’s a trading estate now. That used to be two big pools where they used to pump all the acid water and the alkaline, everything the factories didn’t want went in there. Every time you went it was a different colour. That was levelled off eventually, but was the reason it used to flood, the clay pits here, the mounds, wouldn’t let the water away, and the drains at that time weren’t capable of doing anything with it. So it would flood.’

Artwork, 1.2 metres x 1.8 metres, charcoal and pastel on paper. Made in Oldbury, with children from Langley Q3 Academy.

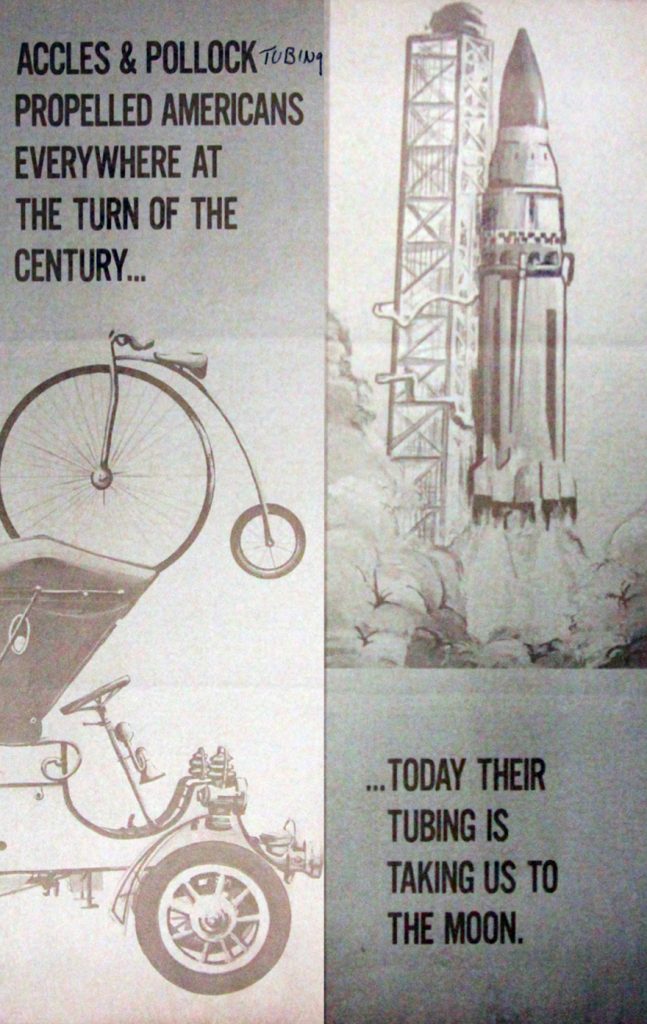

Accles and Pollocks built the world’s first metal-framed aircraft, an elliptical framework meant to carry six people. The Wright Brothers made their first flight in 1903, Louis Bleriot crossed the Channel in 1909, but work on the Mayfly began in 1906. On 7th November, 1910, it was tested at Dunstall Park Wolverhampton, home of the Midland Aero Club.

Designed by a young Royal Navy officer, Lieutenant John W. Seddon, and made with over 2,000ft of tubular steel, it was called the Mayfly. It turned out it was too heavy to actually fly, breaking a wheel on its high-speed ground run, which caused irreparable damage. Repairs and modifications to the Mayfly were then hampered by Seddon’s unavailability due to his service commitments. The aircraft

was dismantled by souvenir hunters.

Nevertheless, by the 1950s Accles and Pollock were supplying metal tubing for retractable undercarriages, airframes and jet engines, for every aircraft built in Britain. Later they even supplied parts for American rocket ships and the Apollo missions.

The future was being made in Oldbury.

Artwork, 1.2 metres x 1.8 metres, charcoal and pastel on paper. Made in Oldbury, with children from Langley Q3 Academy.